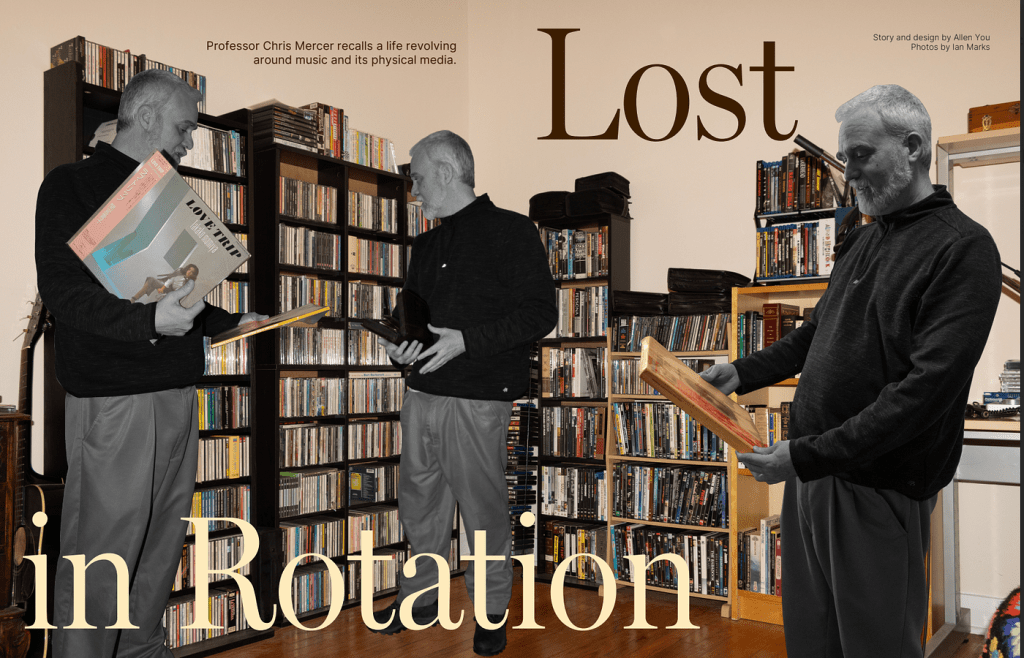

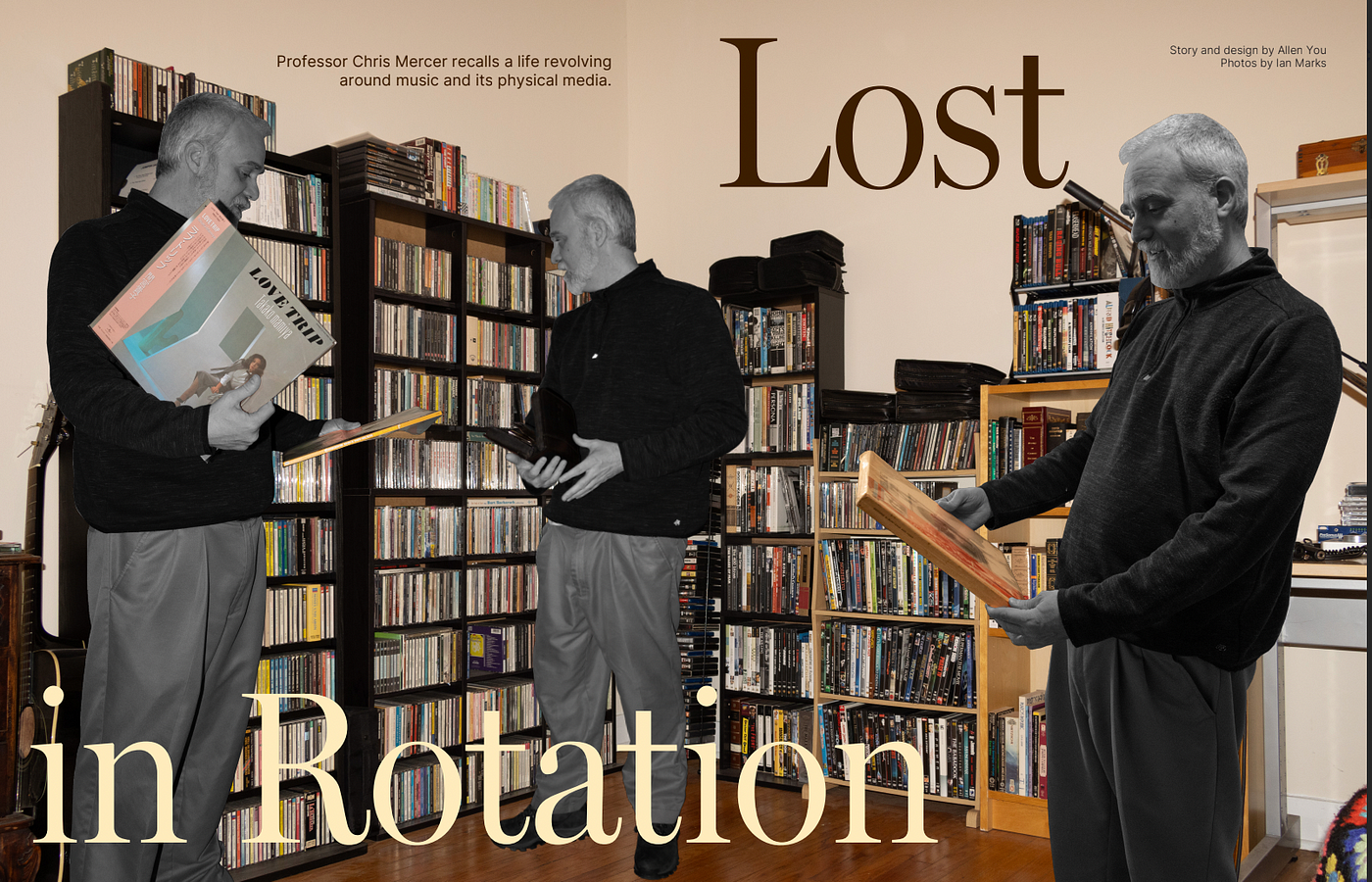

In December 2023, I sat down with professor of music technology, lecturer and composer Chris Mercer to talk about vinyl and CD collecting, his record label and the bygone era of music listening before streaming.

What motivated you to pursue music?

Chris: Basically, listening to records, and in particular, film music. So, film scores in the late 70s, early 80s. A lot of John Williams: “Star Wars”, “Close Encounters”, “Jaws”. And then Jerry Goldsmith, so: “Star Trek: the Motion Picture”, “Alien”, all of that music. I had all those soundtracks, and that pretty much got me interested in being a composer at a young age.

How did you acquire records when you were young?

Chris: My dad owned an electronics store. Back when I was a kid, he worked at RadioShack, which is, I guess, gone now. Then, he worked at another electronics store and eventually had his own electronics store. So I spent a lot of my childhood being babysat in the back of RadioShack… explains a lot. And so there were all these dudes there — these 20-somethings who were into records and worked for RadioShack. And I learned a lot just talking to them, and just hanging around the store and finding out about stereo equipment and records. For a long time, my dad worked in the mall. So I’d go down to the record store and bring records back to his store.

What are your collection’s most prized possessions?

Chris: I have some great Beatles stuff. And then I’ve got a copy of Madonna’s “Like a Prayer” that smells like perfume for some reason. I’ve had it for like 25 years. It still smells like perfume. I’ll let you smell it. It’s really strange. I’ve kept it kind of sealed, so it’ll keep that smell.

Why did you and Prof. Hans Thomalla decide to start your record label, Sideband Records?

Chris: It started with Hans wanting to release some material of his and realizing that making our own label would actually be a more efficient and cheaper way to do it than going through a label. We’re talking about contemporary classical music here, so it’s fairly esoteric… fairly small audience. But no matter who you are, if you get an album made by a label, you’re paying for it. Even Michael Jackson basically had to pay for his albums to be made. It worked out fine for him, but even at the biggest level, theoretically, you don’t start making money from the records you sell until you’ve paid the record company back for the advance and for the investment they made in producing and marketing your album. So we realized that it would be a very efficient way to release our own music, and we also thought while we’re at it, well, we know lots of people who could probably benefit from this. So why don’t we just help them out too? Hans found us an excellent designer, who kind of created a template for all the albums, and we had a really good time doing it. We’re kind of on hiatus from it at the moment, because it is just a labor of love. We don’t make a dime.

What effect has the Internet had on music consumption?

Chris: It’s hard to say because the internet has also diluted the audience a lot. There’s so many options and so many options really tailored to you. Maybe for some people, it makes them less adventurous because they get into a silo. On the other hand, stuff is available in a way that it’s never been when I was a teenager. So it’s never been easier to find out about whatever you want to find out about. But I wonder if it’s less of an adventure… it used to be a little more detective work.

Why do you think there’s a resurgence of vinyl collecting in new generations?

Chris: I think that people really find they can connect with music they like a lot. If it’s physical, if they’re putting it on and dropping a needle and have a big gatefold to look at, it’s compelling. I listen to music on YouTube and other places just like everyone else, but I find it very drab, just really dull. It’s just another click in your life, which is very different from, “Oh, this record needs cleaning, and the stylist needs cleaning,” and that whole ritual is actually really engaging, really compelling. Also records, in a way, sound better. So take Taylor Swift. I have “Speak Now” on vinyl.

That’s my favorite.

Chris: That’s my favorite, too. And I have it on vinyl because when I was listening to the sound files and the CD, it was loud! It was so loud! They master things really loud nowadays, digitally. You can’t get away with that with a record. The physical medium won’t let you make it that loud. It’s mastered in a way that’s less aggressive. So I think that, whether people realize it or not, they may be enjoying the fact that the music sounds better on that level.

What do you remember about burning CDs and that era of acquiring music?

It was really exciting when — this is ‘96-’97 — you could burn your own CDs. It meant that you could burn your own music on a CD, which at the time was like, “Wow, okay, I can go home and listen to my own music on the CD player.” In ‘97-’98, the original Napster came along and you’d spend 45 minutes downloading a three minute song. It was quite the adventure. And they were true mixtapes, because it was just whatever you could find the evening before, however much time you had to download tracks. You’d burn all that to a CD, keep it on a hard drive, but burn it to CD, and listen to it in the car. So I have very fond memories of that. But also that was when you could begin to rip your friends’ CDs. And so suddenly your music collection is getting a lot bigger, because you can take a stack of your friends CDs and rip them all.

I wasn’t around for this, but also Limewire as well.

Chris: Yes! Limewire.

So yes, the early internet days.

Chris: Well, it was amazing because you could find obscure stuff. You could find your favorite artists’ demos and unreleased tracks and stuff like that if you had the patience to sit there for long enough and find it all. It was just whoever was on at the same time. It wasn’t like a database. It was if they were online and they would let you take it. But sometimes people would stop you. You go to download a track and they’d be like, “Nah, you’re not taking it.” Or they get offline because they didn’t want to share it. The worst is: it’s a three minute song, you’ve been downloading it for an hour, and somebody bails on it.